How to Survive and Thrive Paddling in Cold Weather

By Teresa Patterson and Dale Harris

Those who survived Snowmageddon understand that cold weather can be a serious issue even her in the Lone Star State. Many people assume that there is no good paddling in the winter, that all kayaks and canoes and fishing gear should get packed away once the thermometer drops. I am sure the Eskimos would find that very amusing. The fact is that some of the best paddling and fishing adventures happen in the winter—especially here in Texas—when there is actually water in the rivers and lakes and you are not getting baked by the Texas sun. We do most of our recreational paddling in the winter because we love getting out on the water, but hate hot weather and high humidity. From October through April algae is down, bacteria is down, and the bugs and snakes are mostly gone. There is also very little stagnate water, and Bass, Perch, Trout, and Crappie are active and hungry.

But to take advantage of winter on the water and be safe, you do have to take a few precautions and do some careful planning to stay safe and comfortable out on the water.

Plan Before you Paddle

Your paddle preparation will be dependent on they type of water you plan to paddle. Rivers and creeks have different challenges than open lakes.

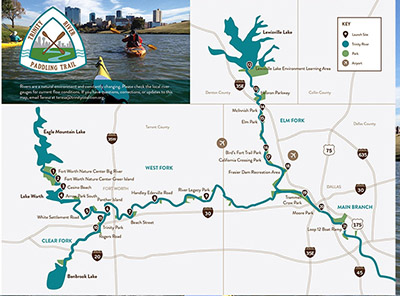

If you plan to paddle on a river or a creek you must check the flow levels (measured in cubic feet per second or cfs). If the flow is too high it will be too dangerous to paddle. If it is too low you might be walking rather than floating. The USGS has flow gauges available for almost all creeks and rivers. Unfortunately, if you do not know the good levels for a given creek or river, the number on the gauge will not help you. You have to find someone who knows the good numbers for that section of water. But never fear, if you are planning to access any of the sections of the Trinity River National Water Trail, there are actually color-coded gauges available on the website: https://trinitycoalition.org/water-levels. These are color coded for each section as low, medium, high, or dangerous. Knowing those levels will also help with planning for nearby creeks connected or related to the Trinity. For cold weather paddling you want to stick with low or medium flows as high water can cause capsize or entrapments that are much more dangerous in cold conditions. Many fishermen and paddlers prefer small to medium sized rivers for cool and cold weather paddling. This means rivers and creeks that have no more than a few riffles or class 1 rapids. These types of waterways are typically easy to stand up in or get to the bank within a few seconds. Being able to get out of the water quickly is key to surviving a cold-water dunking.

If you plan to paddle on a lake there is no real current to worry about, but wind and boat wakes are still a serious issue. On a lake you must check the weather forecast—especially the wind speed and thunderstorm chances. Usually winds over 12 to 14 mph are the limit for any but seriously experienced paddlers. And winter winds at or above 14 mph are not much fun for most experienced paddlers either. High winds are dangerous because they cause waves and chop, which makes a capsize more likely, and makes headway against the wind difficult. Cold wind also ads an additional level of danger because of the wind chill factor. If the winds are up—choose a creek or high-banked river instead. If there are thunderstorms—stay off the water all together.

The basic weather of the day also makes a difference. But when you are planning, remember that temperature is not the whole picture. 50 degrees on a sunny day can be quite pleasant. 50 degrees on an overcast damp day can be completely miserable. Use reliable weather apps to check the weather and plan ahead.

Once you decide the weather and the water are good, make sure you have a paddle buddy going with you, and that someone on shore knows where you are going and when you plan to be back. You should never paddle alone. But this is especially true in the winter when a little help from a friend can make the difference between a mildly uncomfortable capsize and a deadly situation.

Make A Check List

It is important to create a check list that you can adjust and reuse for every trip. If you are just going out for the day your list will be different than if you are going out for the weekend and camping. That list should include a grab bag, which is a dry bag with all your key essentials that you can grab off the boat in an emergency.

Prep Your Boat

It is important that your boat be outfitted to maximize safety. Start by making sure you have a bow line attached to your boat. When you are floundering around in the water it is not a good time to start looking for a rope. Make sure to coil and stow the rope so it cannot come loose accidentally and cause and entrapment situation. Make sure you have a method for removing unwanted water. In warm weather extra water in the boat is just a nuisance. In cold weather it is a serious hazard and will drop your temperature fast. Pack a hand bilge pump, or a bailer, along with a sponge. Bailers work best for large open boats or canoes. Bilge pumps work best for smaller kayaks with tighter cockpits. All boats need a sponge. Most hand pumped bilge pumps work best with a small length of hose or tubing to allow the water to make it to the outside of the boat.

Safety

Safety gear is more important in the winter than in warm weather. First and foremost is your PFD (personal flotation device). It is important that your PFD, or “life vest” be a good one. And it must be actually ON YOUR BODY while you are on the water—especially in cold water where buoyancy could mean the difference between survival and drowning. Especially if something causes you to lose consciousness or the cold takes away your ability to swim. A good vest also allows you to keep many safety items close at hand. Items you should always have in your vest include:

a. Whistle

b. Knife

c. Tow line and carabiner—also known as an “ox tail” This is an 8 to 14 ft length of static line attached to a carabiner that doubles as an extra bow or stern line, an emergency tow line, or extra support when helping someone climb up a steep bank. You also want to keep your phone either in your vest or attached to your body in a waterproof container. It is a good idea to add a small waterproof light and, these days, an emergency mask. We usually throw and emergency snack and some lip balm in there just in case.

Next is your Grab Bag. This must be a bag you can easily get out of the boat in an emergency. It should contain at least:

a. First aid kit

b. Dry change of clothes

c. Fire starters

d. Emergency blanket

e. Whistle, knife, life straw (there should also be a whistle and a knife in your PFD)

f. Dry bag or box for your phone (if it is not on your body)

g. Rain Gear. Preferably gore tex or similar material

h Waterproof duct tape in case an emergency repair is needed.

Your grab bag will vary over time, as you add and fine tune it for your particular paddling or camping style. But it should always contain the basics. If you do a lot of paddling on creeks with deadfalls and log jams, you might want to add a small saw. If you are going into the deep wilderness away from cell signals, or onto a large body of water you might want to add a mini air horn, mini flares, or a GPS receiver, sat phone or sat link. A good GPS receiver will have the capability of doing SOS and Text communications via satellite.

Also pack plenty of drinking water and a few snacks packed. If you get dehydrated or run out of fuel you won’t be paddling anywhere.

It is also a good idea to carry a throw bag. This is a special bag filled with 50 to 75 feet of rope that can be used to rescue a swimmer in the water and pull them to safety. It also has about a thousand other uses.

But gear alone cannot keep you safe. It is important to know how to rescue a capsized paddler and how to be rescued. Self-rescues are much more difficult, but always good if you have practiced. Best to make sure you do not need rescuing by practicing your brace. And, if you have the right type of boat, learn to roll. Take a class or attend a rescue clinic if you do not know how to do these things. In the summer, not having a rescue just means at worst a long swim to shore in your vest. In the winter, it can be deadly.

Now that the boat is outfitted, what do you wear? In the summer a hat, good water shoes, bug repellant and sunscreen are the main requirements. If you get it wrong you get a little sunburnt or have to deal with bites. In the winter what you wear can make all the difference between a fun safe paddle and a miserable or fatal one. The main danger in cold water is not hypothermia, as many believe, but cold water shock. Cold water can literally shock the body and make it start to shut down. If you are immersed in extremely cold water without the proper gear you will lose the ability to swim or move long before you become hypothermic. If you do not have a properly fitted life vest on, this alone is deadly. Cold water can also cause heart failure and stroke. And water temperature is not like air temperature. According to the National Center for cold water safety any water below 70 degrees must be treated with caution. Cold shock can happen in 50 to 60 degree water depending on your level of sensitivity.

Rule number 1. Always dress for the water temperature—not the air temperature. To decide what to wear I use the 120-degree rule. If the water temperature and the air temperature together add up to less than 120 degrees, you should only paddle with specialized cold weather gear. That means wet suit or dry suit or equivalent.

But there are a lot of levels of clothing between summer swim wear and dry suites that are appropriate for most Texas winter paddling and for tight budgets.

Clothing:

For cool weather paddling you should only wear fast drying fabrics such as nylon, polar fleece, poly blends, as well as other man-made materials. Wool and smart wool also work for cool weather paddling. The fabric you must avoid is cotton. That means no denim and no cotton T shirts. Never wear cotton on the water in the winter. COTTON KILLS. It becomes heavy and traps the cold close to your body and does not dry well or quickly. So, if you can’t wear cotton, what should you wear instead?

Dry Suit

The gold standard for winter paddling is, of course, the dry suit. A good paddling dry suit has neoprene gaskets at the neck and wrists as well as a waterproof zipper. The good ones are constructed of breathable material to allow air flow in. Your level of warmth will depend on what you wear under it. In milder temperatures wear a basic base layer legging and top with moisture wicking properties. In colder weather wear fleece or polar fleece, possibly in addition to the base layer if you are particularly cold natured. Not only will it keep you warm, but even in the event of a capsize, it will keep you dry. This is very important as water will steal your warmth even after you get back in your boat. But if only your hand and face are wet, it is much easier to recover.

PLUSES: The reason it is the gold standard is that it does what it says it will do—keep you dry even when immersed in water. And when you are dry the cold is not as dangerous. With the right undergarments you can even be comfortable when immersed in icy water. If you plan to paddle rough water or white water in the winter the dry suit is a MUST.

DOWNSIDE: Dry suits are expensive and must be maintained. They can cost more than $1000.00. Although there are some on sale this season as low as $400. But that is still more than most casual paddlers want to spend just to be able to paddle in the winter.

Dry Top and Bottom

The next, much more affordable option is to go for dry separates, such as dry pants and/or a dry top. You only have to buy the one you really need, and possibly ad the other one at a later date. If you are doing a lot of wading to get in and out of your boat or a lot of fly fishing outside your boat, you might want to opt for dry pants and a less expensive top. A good set of dry pants comes with footies and will keep the lower part of your body completely dry so long as you do not immerse past your waist. As an instructor I use mine a lot and the usually run a lot less than half of a dry suit. Dry tops are a good choice if you mostly need protection from water splash or if you usually wear a spray skirt and have a good roll. A lot of whitewater paddlers opt for this choice and wear spandex or splash pants on the bottom. When worn together they are almost as good as a dry suit—but almost is not the same as dry. They still leak in the middle if you stay in the water more than a few moments. Dry pants run about $200. Dry tops between $150 and $350.

PLUSSES: Allows a mix and match approach, and is usually a little less expensive than the full dry suit.

DOWNSIDE: You will only stay completely dry if you avoid immersion, they are still expensive for the casual paddler, and many people hate putting on the top with the neoprene gasket.

Splash Wear

For a more affordable, but less dry option, “Splash wear” or Semi dry tops and bottoms are the popular choice. Splash tops and bottoms will keep the wind and water off you so long as you do not become immersed while adding a layer of warmth. You must make sure to put enough fleece or other wicking base layer under your splash wear to be adequately prepared for the water temp if you swim. Splash wear will not help you stay dry in the water, but when you regain your boat, it will keep the wind off you enough to mitigate additional chilling. Splash bottoms do not have footies, so it is important to pair them with a good water boot or water shoe insulated with thick socks and/or neoprene socks.

PLUSES: Warmer and drier than cheaper options. Usually affordable, often under $100 for both.

DOWNSIDE: Will not keep you dry in a capsize. Can cause sweating because of lack of breathability in the material.

Wetsuits

A lot of paddlers also use wetsuits, and that is a valid option. Depending on the thickness, measured in millimeters, wet suits can keep you warm in even very cold water, and there are a lot of choices. The Farmer John, which allows freedom of arm movement is most preferred by paddlers. I myself am a diver and I have plenty of wetsuits, but I really do not like them for paddling unless it is the only cold water gear I have. The problem is that wetsuits are designed to work with the water. They work best when there is a layer of water between your body and the neoprene. The wetsuit traps that water and allows your body to warm it to form an insulating barrier against the cold. But if you are not in the water, you can easily get overheated in a wetsuit, which can make the shock of immersion worse until your body warms the cold water that will flow into your wetsuit.

PLUS: Can keep you warm even when immersed in water and wet.

DOWNSIDE: can cause overheating when not in the water. Can restrict freedom of movement. Can feel very cold after coming out of the water as the wind causes evaporation. Good ones are almost as expensive as dry gear.

Alternatives:

What if you don’t have access to any of the usual choices? Does that mean you should give up winter paddling? Not necessarily. Sometimes inexpensive options from you closet can still keep you protected. A base layer of Lycra spandex or other athletic wicking fabric, topped with fleece separates, with a waterproof wind suit or workout suit over all, can give a lot of protection from cold, wind, and water. It won’t be as good as most actual paddling wear, but it will be good enough to allow you to enjoy winter paddling until you can acquire better.

Extremities

But what about your extremities? Keeping your hands feet and head warm is least as important as protecting your body. Especially since we lose most of our body heat through our extremities. To protect you head a ball cap is the minimum. If it is really cold a cold weather hat with earflaps and a brim works well. A scuba hood is also very effective—especially when paired with a dry top or splash top since the gaskets will tuck together. If you are wearing a rain or wind suit with a hood, wear a brimmed hat under it to add warmth and prevent the hood from collapsing around your face when you turn your head. And balaclavas, which cover head, neck, and face are always a good choice.

For your hands choose waterproof paddling gloves, dive gloves, sailing gloves, or my favorite, pogies. Pogies are mittens that attach to the paddle shaft and keep your hands warm and dry, but allow you to easily remove your hand at will. I usually use spandex gloves or fingerless gloves in combination with pogies.

Since it is almost impossible to keep your feet dry while kayaking or fishing, having good footwear is critical to a successful outing. A combination of thick socks—preferably smart wool—and neoprene or rubber boots provide the best protection. The number one pick for Texas winter paddling is the NRS Boundary Boot. It keeps feet almost completely dry, but is thick enough to hold warmth even if you do manage to get water inside. Scuba booties are a good second choice. Rubber rain boots are also effective in larger canoes and sit on top kayaks. They do not work as well in sit inside cockpits where foot flexibility is required. Water shoes or sandals with waterproof socks over smart wool can also work, and are much better than water shoes alone. If you get cold hands and feet easily you can always add a chemical heater to your socks or gloves.

Whatever you choose to wear, you must choose something that will keep you warm enough to be able to assist in your own rescue if you capsize, or provide comfortable warmth all day if you manage to avoid going into the water. Winter paddling can provide a wonderland of adventure if you do is safely. See you on the water!

If you enjoyed this article and video please consider donating to Trinity Coalition. Your support is what makes our work possible and helps us to provide support to paddlers and protect our waterways.